Jolene’s stories behind the

West River Mysteries

From Jolene:

Life with my heart in two places began in 1978 when Hiram and I moved from the ice cream capitol of the world in Le Mars, Iowa to a remote part of South Dakota. I was homesick for paved roads, orderly green fields of corn and soybean, and living close to the library and stores. And my family. I really missed my family.

Not surprising since I was twenty-two and away from home from the first time.

The surprising bit began seven years later when we moved back to Iowa, and I became homesick for South Dakota. My homesickness continues to this day, even though my morning walks along the lake are filled with beautiful views. I snapped this picture and imagined what fall must be like in Harding County as the cottonwoods drop their leaves against a backdrop of rugged buttes and short grass prairie.

Life with my heart in two places won’t end as long as I’m on this earth.

Writing fiction is the perfect way to cope with homesickness. Every afternoon I sit in our Iowa living room, open my work in progress and start writing. Immediately I’m in the town where we once lived, surrounded by the children and families I still love. I can smell the crisp, fall air and almost touch the stars hanging low in a sky untouched by light pollution. When it’s time to fix supper, I return to Iowa where a trip to the grocery store for missing ingredients takes ten minutes or less.

So far as life with my heart in two places goes, this is the best of both worlds.

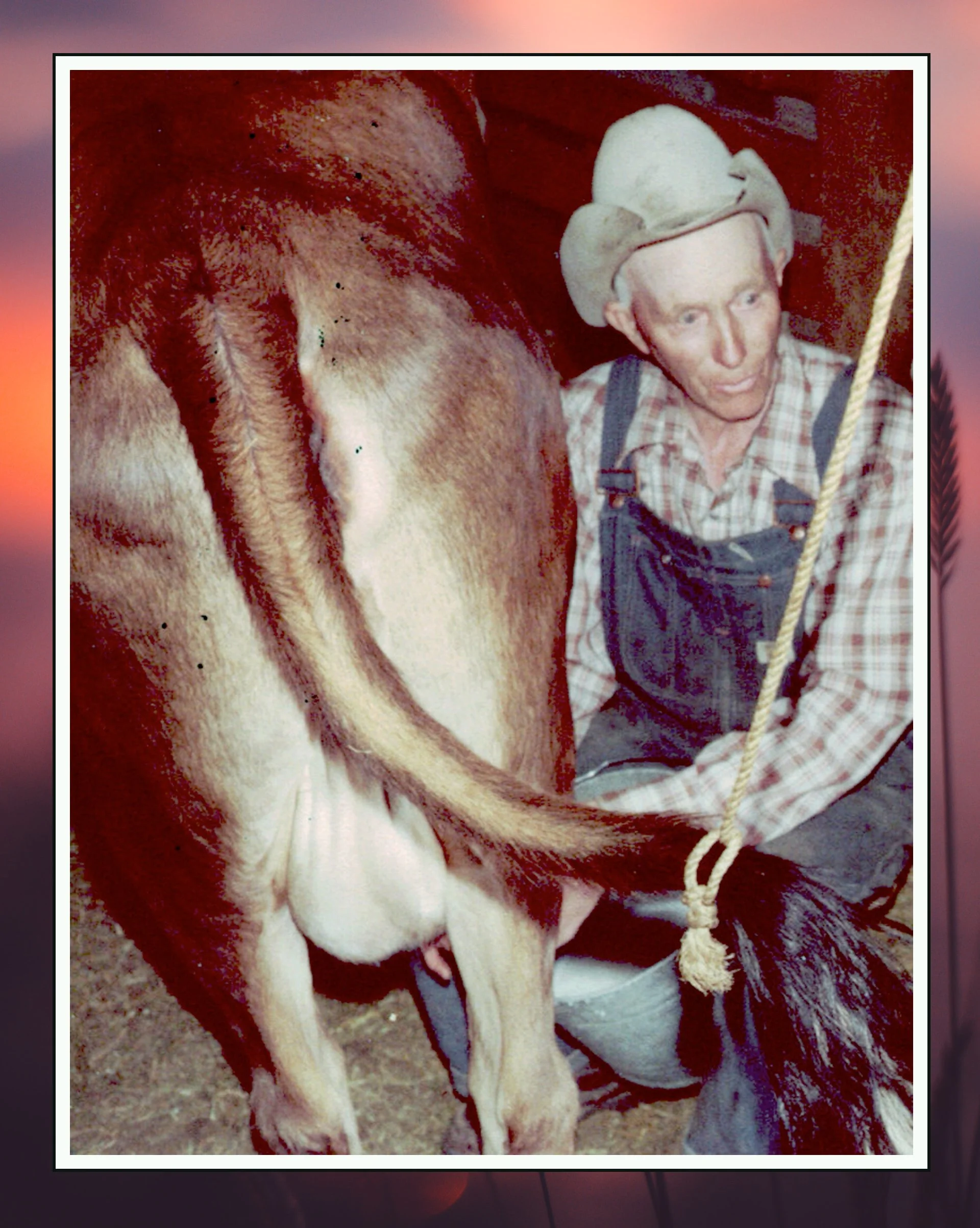

Cows and plot points appear to have very little in common. In See Jane Run!, however, cows and plot points intersect often, starting on page one. Many, though not all, of those intersections are examples of art imitating life. The cow in the photo above is one such case.

The cow’s name was Snippy. The old timer milking the cow was named Walter Stuart. Walter’s farm was right behind the school where I taught in the little town where Hiram and I lived. (I am not making this up.) We and half the town bought fresh milk from Walter for 50¢ a gallon.

Walter was inordinately proud of Snippy and for good reason. Her milk was so rich that every gallon yielded a full quart of cream. Thick, delicious cream that could be whipped into butter or used in cooking.

One day, Walter called my husband and asked him to bring over our Kodak to take a picture of his cow. Hiram took several shots and got ready to leave. Walter stopped him and said, “But you got to take a picture of Snippy’s business end.”

A revised version of this story made its way into See Jane Run! and is an example of art imitating life. In this short excerpt, Jane is the narrator, Merle is Walter, and Snippy is Snippy:

I scooted a few steps to my left to capture Merle and his girl in the best light. I snapped a couple shots and promised to bring him the pictures once the film was developed.

“But we ain’t took the good pictures yet.” He turned Snippy until her head faced the barn door and her backside faced me. Then he pointed at her udder, so full and heavy her teats nearly dragged on the ground. “Now you just squat down and get some Kodaks of her business end. Make it quick. I want to show you my garden and have enough time to eat before she needs milking.”

I framed Snippy’s . . . ahem . . . business end in the view finder and took several shots.

The photographs Jane takes that day play a crucial part in the unfolding of the mystery and its solution. In other words, the intersection of cows and plot points can happen, at least in See Jane Run!

“Bud and Rachel have to be in your book,” my Harding County friend said as we sat down to coffee several years ago.

“But they sold their company to the West River Telephone Co-op the year before we moved to town,” I said.

“That’s a minor detail,” she said. “Besides, you’re writing fiction, right?”

“Okay,” I agreed, “tell me how their phone system worked.”

She didn’t need to describe Bud and Rachel because they and their mule lived in Camp Crook when we did. We saw them from time to time, the most notable being the night before we moved to Iowa in 1985 to be closer to hospitals where our son could be treated for his rare medical condition.

Hiram answered the door and invited Rachel inside.

“Me and Bud wanted to tell you goodbye and to give you this.” She handed us a back issue of the county paper, Nation’s Center News. “There’s an article about me and Bud in there. So you don’t forget us.”

“Thank you,” I said, noticing that she had written “Please look on page 3” above the masthead in spidery letters.

The newspaper clipping

Next she gave Hiram an envelope. “It’s a little traveling money. For emergencies.” She smiled at our son, who’d had lots of medical emergencies since his birth three years ago.

Rachel and Bud were no strangers to childhood medical emergencies. Rachel was born with a cleft lip and palette in 1910 and was spoon fed Carnation canned milk during her early months. Eventually the people in the small Montana community where her family lived raised money so her mother could take her by train to Mayo Clinic for surgery. Bud lost his vision in a 1928 dynamite explosion when he was eleven.

Rachel’s surgery was successful but not elegant. Her speech was difficult to decipher, but she never stopped talking. Bud’s decades-old scars were visible, but he climbed telephone poles and installed phones confidently.

I can’t imagine the West River Mysteries without Gus and Betty Yarborough, for whom Rachel and Bud were the prototypes. Betty is a vital communication (and gossip) hub in a time before cell phones. Gus and Betty exemplify the essential roles people with disabilities can play when given the opportunity to use their abilities.

As for the $35 Rachel and Bud gave us, it was the exact amount needed to pay for a new prescription medication our son needed on the trip to Iowa.

As for the newspaper article, it lives in a file in my office along with my most prized South Dakota memorabilia from our years there.

As for Rachel and Bud, you are remembered.